What inspired the outfits in Margaret Atwood's "The Handmaid's Tale"

In the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library in Toronto, Canada, Margaret Atwood, award-winning dystopian fiction author, fished out an article from a research folder.

"Women forced to have babies," Wertheim read aloud from a news clipping.

"Communists are making women have babies," Atwood clarified. "'Persistent non-pregnancy will be considered a crime against the state,'" she quoted from an old news story about Romania.

Atwood has stacks of research for her novels in these archives. She writes by a strict rule: if it didn't happen, somewhere, at sometime, it doesn't make it into the plots of her stories.

That rule applied to Atwood's most famous work, "The Handmaid's Tale," published in 1985, and later turned into an Emmy award-winning television series for Hulu.

Atwood told Wertheim there were several ways into the story, but an inciting event came in 1981, just after former President Ronald Reagan was elected for the office.

"And this was the moment at which the religious right was getting organized as a political force," she told Wertheim.

"This friend said to me, 'Have you heard what they're saying?'... and one of the visions was that women should be back in the home."

This moment, Atwood explained, also coincided with an increased participation of women in the workforce.

"My question to myself was: now that they're all running around having credit cards and jobs, how are you gonna get them back into the home?"

Atwood cited George Orwell as an influence too, saying, "I had read '1984' as a very young teenager and been extremely impressed by it."

Wertheim asked about the now-iconic red cloaks and bonnets that have become a uniform of political resistance in the Trump era.

"Well, if you have a cult, and if you [have] totalitarianism, you have to have outfits," Atwood told 60 Minutes.

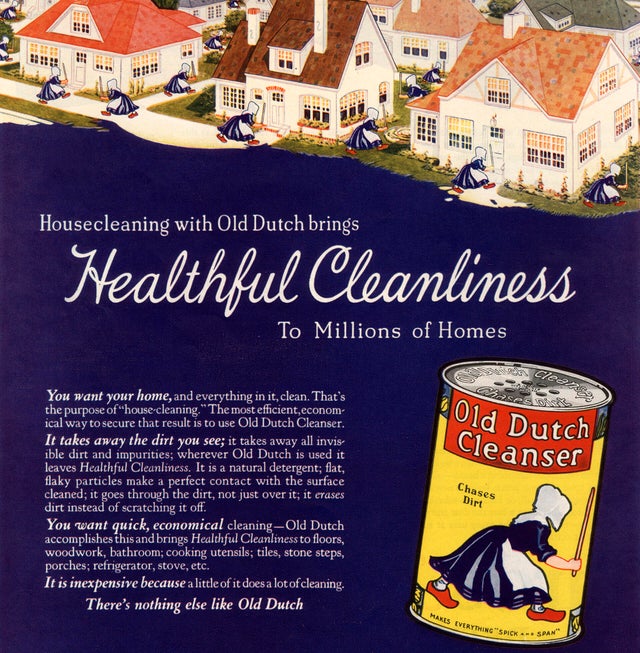

The bonnet-and-cloak outfit was largely inspired by a can of Old Dutch cleaning solution.

"The Old Dutch Cleanser box of the 1940s traumatized me as a child. So it shows a woman whose face is covered by this bonnet, holding a stick and chasing something… pretty scary," she told Wertheim.

"For the 'Wives,' it would be blue, which was the Virgin Mary color," Atwood told 60 Minutes. "[But] for the handmaids, it would be red, which is the Mary Magdalene and 'Scarlet Letter' color."

Atwood is a student of government, power and the overreaches of both.

She wrote much of "The Handmaid's Tale" on a rented typewriter in 1984 West Berlin.

In her ventures to the Eastern Bloc, she witnessed policing, paranoia and the absence of freedom.

Atwood made Harvard University a central location for the dystopian society in "The Handmaid's Tale."

She knows Cambridge well: she was a grad student there in the 1960s.

"It was right in the heart of what people believed– in the 80s, 70s, and 60s, and 50s– what they believed America to be. And what they believed it to be was the antithesis of the USSR," she told 60 Minutes.

"I was very interested in totalitarianism and I was very interested in how they get that way…I didn't like hearing people say, 'It can't happen here [at Harvard].' Because anything can happen anywhere given the circumstances."

"All of the details from 'The Handmaid's Tale' [are] from other countries, other times… they're all real, and I put them right in the heart of liberal America," she told Wertheim.

Atwood wrote one of two dedications in "The Handmaid's Tale" to a 17th century woman named Mary Webster, a.k.a. "Half-Hanged Mary."

Like many other women during that time in New England, she was wrongfully accused of witchcraft and sentenced to death by hanging.

"[She was] taken to Boston, was put on trial, got exonerated… but the townspeople didn't like the verdict and strung her up anyway," Atwood explained.

"[They] came in the morning to cut down the body, and she was still alive… I expect if they thought that she was a witch before this event, they really thought so afterwards. But they didn't hang her again. And she lived another 14 years."

"You traced this. This was a relative?" Wertheim asked.

"On Mondays, my grandmother said it was [a relative]," Atwood said.

"And on Wednesdays, when she was feeling more respectable, she would say that she wasn't so sure."'

The video above was produced by Will Croxton. It was edited by Nelson Ryland.