Scene after Russian strike on Ukrainian bus was all "mud, dust, blood, crying and bodies," prosecutor says

Russia's bombardment of Ukrainian cities is relentless as Vladimir Putin tries to plunge civilians into a winter of cold and darkness.

President Putin's war, approaching four years, threatens to draw in all of Europe. Targeting civilians has been an international war crime since 1949. The crimes you're about to see are hard to watch. Putin is hitting homes, schools, hospitals, and seven months ago, a city bus. In the city of Sumy, Bus Route 62 takes you to the university, the mall and on to the airport. The fare is 20 cents. Last April, Palm Sunday, there was only standing room as two ballistic missiles bolted through the sky of a clear, holy, day.

The body is wrapped to preserve the evidence in the hope of a future trial. But a Ukrainian war crime prosecutor wanted us to see it, wanted the world to see the steel corpse where 16 civilians were killed.

We climbed aboard with prosecutor Vitalii Hovhal who showed us the shrapnel that sliced through the bus.

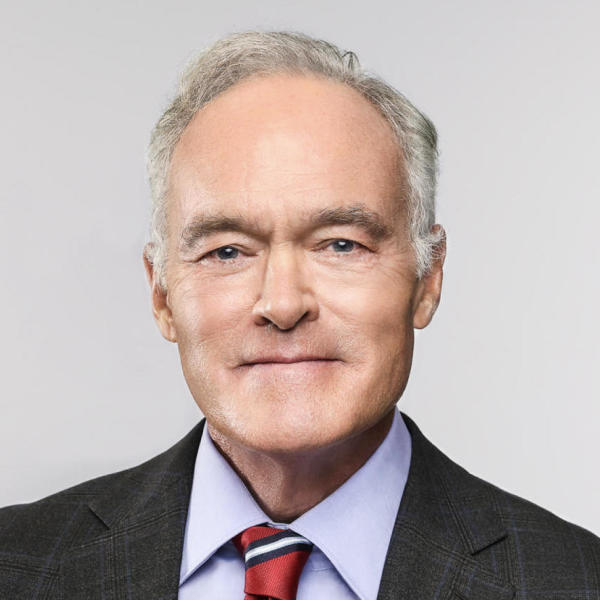

Scott Pelley: This is from what the military calls an anti-personnel warhead. It's designed to kill as many people as possible.

Vitalii Dovhal (translated): And it doesn't [distinguish], whether it's a soldier, or a child, or a retiree. This little square will not spare anyone. And this is exactly why this is a war crime.

The crime scene is a city of 250,000 less than 20 miles from Russia. Most days in Sumy are interrupted by an air raid. And so it was last April 13, Palm Sunday, for passengers on Bus Route 62. Tetiana Pohorelova was taking Lisa to her grandparents.

Tetiana Pohorelova (translated): Lisa is a little girl. She wants to pick her own outfits, and we are always late. I wanted to catch that bus. The next one wouldn't come for an hour.

Natalia Tenytska and her son, Maksym, were headed to the mall.

Natalia Tenytska (translated): It was the day before my son was going to have his school picture. We were going to buy some nice clothes.

On one of Ukraine's holiest days, the bus happened to be on Peter and Paul Street. At the same moment, a warhead was bearing down, with great precision, at 2,000 miles an hour … one blow on more than a dozen cameras.

Natalia Tenytska (translated): It got dark inside. My ears started ringing. People were shouting to open the doors.

Tetiana Pohorelova (translated): The first thing I thought was that I could feel my body. I thought, 'okay, I can feel everything, Lisa is screaming so, we're alive.'

Lisa's screams carried on into the street. Tetiana is saying to her daughter, "Wait my little sunshine. it's going to be alright. You have a little cut, a little cut."

Tetiana Pohorelova (translated): Everything looked destroyed. I saw broken branches. There was the smell of burning and soot. And there were people lying on the ground... people who—you understand.

Maksym (translated): In the front of the bus, everyone was dead. I was walking on dead bodies.

Natalia Tenytska (translated): I urged him to leave [me] and run, but he said, 'No, that's never going happen.' He broke what was left of the window with his feet, so we could escape.

That's Natalia and Maksym, among 25 surviving passengers. Many others, on the street, were cut down. In the lower right corner, a 47-year-old musician, a pianist, Olena Kohut had watched the bus pass.

Hit by shrapnel. bleeding out. she would live — two more steps.

Altogether, 35 civilians killed, two children —and 145 wounded.

Prosecutor Vitalii Dovhal responded from his church. He told us:

Vitalii Dovhal (translated): I have never seen such a horror in my life.

Vitalii Dovhal (translated): Lots of people were lying on the pavement. I saw that bus that had burned.

Vitalii Dovhal (translated): It was all mud, dust, blood, crying and bodies.

Scott Pelley: You seem to be saying this isn't war, this is murder.

Vitalii Dovhal (translated): In my opinion, yes. It is just unimaginable to use such powerful, high-precision weapons in the central part of a city.

Dovhal's investigation shows there were two missiles, among the most accurate in the Russian arsenal. The first wrecked Sumy State University's conference center. The second, Peter and Paul Street. They're among hundreds of Russian war crimes and we have seen many over the years in Ukraine: a school in Chernihiv, a hospital in Izium, apartments in Borodianka.

Scott Pelley: Mr. President, I'm glad to see you again, sir.

Volodymyr Zelenskyy: Thank you for coming.

Last April, President Volodymyr Zelenskyy met us on a playground where a missile killed nine children and 10 adults.

All of those, so many more, and now this, make Ukraine the largest crime scene in the world. Ukraine's top prosecutor told us that the number of war crime investigations now open at the beginning of the fall, is 178,391.

Beth Van Schaack: They are systemic. Literally, everywhere that Russia's troops have been deployed.

Few know the big picture like Beth Van Schaack. Until recently she was U.S. ambassador-at-large for global criminal justice. She directed American support for Ukraine's investigations.

Beth Van Schaack: Attacks happen in towns and villages where there are no discernible military objectives. The attack seems to be calculated to make as much destruction as possible and to terrorize the civilian population. So, it's an effort to subjugate and to terrorize the community in order to get the country to essentially capitulate.

The reason for Russia's terror is to take back territory it lost with the fall of the Soviet Union. Ukraine won independence 34 years ago. It's a democracy about the size of Texas. Of all of the crimes here, Putin faces one arrest warrant. In 2023, the International Criminal Court charged him in a campaign against Ukrainian children.

Beth Van Schaack: He is accused of abducting Ukrainian children in a systematic way. It's a war crime. It's a war crime of unlawful transfer of civilians, and in this case dozens and dozens of Ukrainian children.

Scott Pelley: And these children are being kidnapped?

Beth Van Schaack: They're being kidnapped. They're being subjected to Russification, to military training. They're forced to deny their Ukrainian roots. And ultimately, they're often put up for adoption or placed in foster homes in Russia.

Scott Pelley: What is the point?

Beth Van Schaack: The point is to ultimately undermine the idea that Ukraine is an independent country and to raise these children as Russian children who deny their own cultural heritage.

Putin and his allies who are secure in Russia, are unlikely to face justice. But Ukraine is holding trials. There have been 211 convictions, many Russian troops, though nearly all of the defendants are at large. Still, prosecutor Vitalii Dovhal has patience. He showed us where evidence for future trials is warehoused, including crashed drones and mangled missiles.

Vitalii Dovhal (translated): On each part we find a serial number. We identify the part, where the part was manufactured and when this missile was assembled in a factory.

In the Palm Sunday massacre, serial numbers, like fingerprints, identified Russian ballistic missiles with 1,000-pound warheads. Ukrainian intelligence pinpointed the Russian units involved.

Vitalii Dovhal (translated): We already know the individuals who gave the orders to carry out the attacks.

Scott Pelley: Do you have any reason to hope for justice?

Vitalii Dovhal (translated): I am convinced that those responsible for the strike at the central part of the city on Palm Sunday will be punished. The military commanders who made the decision to launch these missiles. I am convinced.

Natalia Tenytska (translated): They're killing civilians. It's elimination of the Ukrainian nation. They're just wiping our cities off the face of the earth.

We interviewed Maksym and Natalia, Tetiana and Lisa in the conference center destroyed by the first missile. We could see where the warhead crashed through to the basement. The Russians claim they were aiming at a military awards ceremony. But prosecutor Vitalii Dovhal says that doesn't explain how no troops were hit and why two missiles fell on civilians.

Scott Pelley: You have quite a stake in the future of Ukraine, and I wonder what is your hope?

Tetiana Pohorelova (translated): I would like the Russians to answer for what they've done. I don't wish death on those people. I want them to learn how it feels to live in fear. I wish Ukraine could see the end of the war. And I want people to be able to live in their own homes. That's it.

Near our interview, we found a room where, it looked to us, like a victim may have fallen. Close by, in the bomb dust on the table, someone had drawn a line. we don't know what they meant, but with so many innocent victims murdered without justice perhaps the question was "why?"

Produced by Nicole Young. Associate producer, Kristin Steve. Broadcast associate, Michelle Karim. Edited by Peter M. Berman.