University of Chicago researchers develop new and highly sensitive test for PFAS, or "forever chemcials"

Synthetic PFAS are known as "forever chemicals," lingering in water, cookware, cosmetic products, clothing, and even our blood as they resist breaking down. They're infamous for being hard to detect.

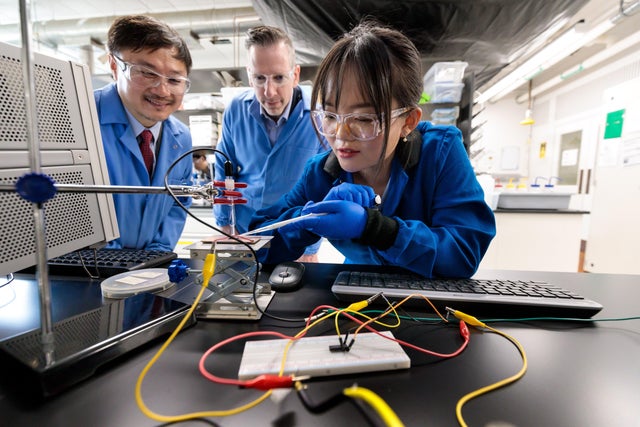

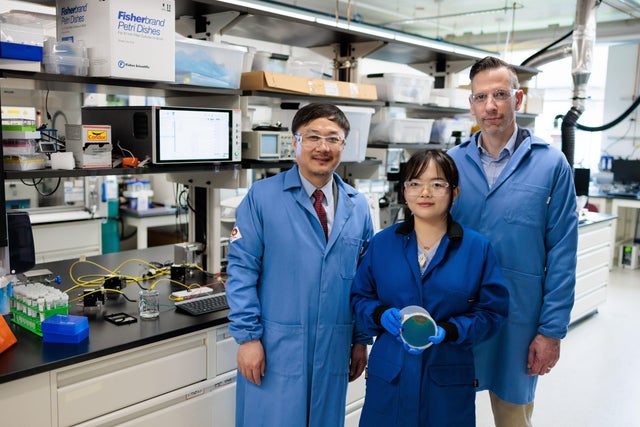

But researchers from the University of Chicago's Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering and the U.S. Department of Energy's Argonne National Laboratory have devised a new method to detect minuscule levels of the synthetic compounds in water. The method involves a portable, handheld device, UChicago said.

PFAS stands for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances. The chemicals resist grease, oil, water, and heat, and have been linked to cancers, thyroid problems, and weakening of the immune system.

According to the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, PFAS do not degrade easily in the environment because their molecules have one of the strongest bonds. Because of this, They break down slowly, if at all.

Junhong Chen, Crown Family professor at the Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering and lead water strategist at Argonne, emphasized how levels of the substances are also hard to detect.

"Existing methods to measure levels of these contaminants can take weeks, and require state-of-the-art equipment and expertise," Chen said in a news release.

But Chen said the new sensor that he and his team developed can detect the chemicals in minutes.

UChicago said the technology can detect PFAS at 250 parts per quadrillion. This goes beyond the metaphorical finding a needle in a haystack — the university said it is the equivalent finding a lone grain of sand in an Olympic-sized swimming pool.

The new technology will be useful in monitoring drinking water for two the most toxic PFAS — perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS), the university said. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency recently proposed limits of 4 parts per trillion for the chemicals, but Chen said enforcement of such limits currently runs into the issue of how time-consuming it is to detect PFAS.

"You currently can't just take a sample of water and test it at home," Chen said in the release.

Currently, the gold standard for PFAS level measurement is an expensive laboratory test called liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry, which separates out the chemical compounds and breaks down information about each one, the U of C said.

Researchers trying to develop faster and cheaper PFAS tests have run into problems. UChicago noted that PFAS are often present in water at far lower concentrations than dozens of other more common contaminant chemicals, and further, there are thousands of different PFAS that barely differ at all chemically, but vary greatly in terms of health effects.

But for the past 15 years, Chen's team has already been developing sensitive portable sensors on computer chops — and the team is already using the technology for detecting lead in tap water, UChicago said. It turned out that the technology was useful for PFAS sensing too.

The way the detection device works is that if a PFAS attaches itself to the sensor, it changes the electrical conductivity flowing across the surface of the device's silicon chip, UChicago explained. Chen and his colleagues had to figure out a way to make each sensor highly specific for one given PFAS chemical, and for that, they turned to artificial intelligence and machine learning.

"In this context, machine learning is a tool that can quickly sort through countless chemical probes and predict which ones are the top candidates for binding to each PFAS," Chen said in the release.

In a new paper on their research published in the journal "Nature Water," Chen's team showed that one of the probes sorted by machine learning selectively binds specifically to perfluorooctanesulfonic acid — even when other chemicals are in the same tap water sample at might higher levels. The conductivity of the chip in the sensor will vary depending on the level of the chemical, the university explained.

The team worked with the EPA and used the older liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry methods to verify their results, the university said.

Down the line, the technology may allow consumers to test their own water for PFAS, the U of C said.

The most prestigious universities in the Chicago area have been at the cutting edge of research on PFAS. Back in the spring, Northwestern University professor of chemistry SonBinh Nguyen and professor of engineering Tim Wei developed a graphene oxide solution that is water- and oil-resistant and could be a replacement for PFAS in items such as takeout coffee cups.